Vinews

No. 14 — July 1, 2019

Contents:

- Grapevine Trunk Diseases: What Richard Smart Found in Missouri

- Phytotoxicity: Be Careful With the Spray Cocktails

- Rupestris Speckles Masquerades Ability to Diagnose Early Downy Mildew Symptoms

- IA 20x Hand Lens Can Save You a Lot of Misfortune

- Grape Exchange

- Cumulative Growing Degree Days for the Seven Grape Growing Regions of Missouri from April 1 to June 24, 2019, and from April 1 to July 1, 2019

Grapevine Trunk Diseases: What Richard Smart Found in Missouri

The flying vine doctor, Richard Smart, was in Missouri last week to provide education, consulting and wisdom on canopy management and grapevine trunk disease. I was fortunate to spend more than 30 hours with Dr. Smart. Over that period of time, we covered the gamut on canopy management and trunk diseases. For those of you unfamiliar with Dr. Smart’s contributions to viticulture, his contributions are immense and he is very well known for his book “Sunlight into Wine." Over the last two years, Dr. Smart has been traveling among eastern USA vineyards and diagnosing grapevine trunk diseases (GTD). In 2018, Dr. Smart and Mike White from Iowa State University visited Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska and Illinois. In 2019, Dr. Smart visited New York, Quebec Canada, Michigan, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri. What did Dr. Smart find in common in all of these states?

Grapevine trunk diseases were prevalent in all these eastern viticulture states as well as in Quebec, Canada. A common theme occurred across this wide geographical area. Many of the vineyards that are experiencing vine decline where vines have dead spur positions, blank wood along the cordon, etc. In most cases, vineyard managers were pointing their fingers at winter cold damage. Certainly the polar vortex of 2013 and 2014 did some damage. However, as Dr. Smart demonstrated, he has observed vines in warm climates such as Australia or South Africa that have the same type of symptomology as he observed in declining vines here in Missouri and other eastern viticulture states.

Grapevine trunk diseases are very different compared to the foliar diseases of grapevines. Trunk disease microorganisms are epiphytic. The grapevine and the epiphytic microorganism can live in harmony together and the epiphytic microorganism does no harm to the grapevine initially.

The epiphytic microorganism at some point becomes a pathogen and starts to cause harm to the semi-permanent wood (trunk, cordon and spurs). The change from friend to foe by the epiphytic microorganism is believed to result from vine stress(es). Dr. Smart pointed out that these stresses can include saturated soils, drought and cold winter temperatures. Missouri being a continental climate experiences cold temperatures, drought and recently this spring saturated soil conditions.

One of the more common grapevine trunk diseases is Phomopsis (Phomopsis viticola). Most of you are familiar with Phomopsis as foliar or shoot pathogen. Phomopsis infects grapevines early in the season during cool wet conditions. In 2018, Mike White sent several grapevine trunk disease samples to laboratories for identification. Many of these samples came back positive for Phomopsis. Dr. Smart pointed out that Phomopsis was first reported in a paper from New York 108 years ago and that Phomopsis has been largely ignored as a problem. However, I have been advocating for years that if you want to prevent Phomopsis infections, it is critical that early season protective sprays need to be applied at 0.5- to 1-inch shoots, especially when environmental conditions are wet and cool.

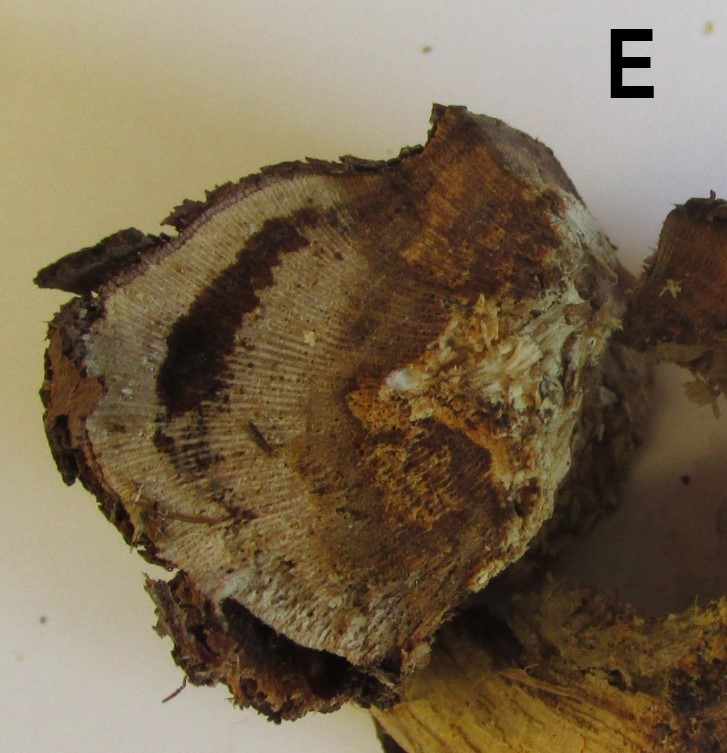

Dr. Smart and I collected more than 25 samples (Figure 2 shows a small sampling of the symptomatic wood) of grapevine trunk disease from Missouri vineyards. I am hoping to have all these samples evaluated by a laboratory specializing in grapevine trunk diseases. This preliminary survey will provide information on prevalent grapevine trunk diseases here in Missouri. The last information on grapevine trunk diseases in Missouri was published by José Ramón Úrbez Torres who spoke at the Missouri Grape and Wine Conference and Symposium in March 2019. Further research is being conducted by graduate student Emily Serra in the laboratory of Dr. Megan Hall of the Grape and Wine Institute. Hopefully, through research and educational outreach through MU Extension, more answers can be found in managing grapevine trunk diseases.

Current management practices for grapevine trunk diseases includes preventative practices to reduce infections, trunk renewal and sourcing grapevine trunk disease free planting material. Grapevine trunk disease microorganisms can enter a grapevine through wounds. Some of the most prevalent wounds are pruning wounds in spur pruned grapevines. Dr. Smart recommends treating these pruning wounds with labelled fungicides or other materials that block the entry of grapevine trunk diseases from entering the pruning wound. Prior to suggesting prophylactic protection with fungicides, I would like to know when the grapevine trunk diseases are releasing infective spores. In addition, I would like to know what are the most destructive grapevine trunk diseases we are battling here in Missouri. Trunk renewal is a method to eliminate trunk disease in an infected vine. Dr. Smart suggests that trunk renewal should be initiated when a vine starts to show decline. In some cases this renewal may be on what most would consider very young vines (3 years). However delaying trunk renewal on a grapevine disease infected plant may preclude trunk renewal as an option. If the grapevine trunk disease moves into the soil/shoot junction then trunk renewal cannot occur. Dr. Smart recommends that uninfected wood should be 10 to 12 inches away from the infected wood. Planting grapevine disease free planting material is another way to manage grapevine trunk diseases.

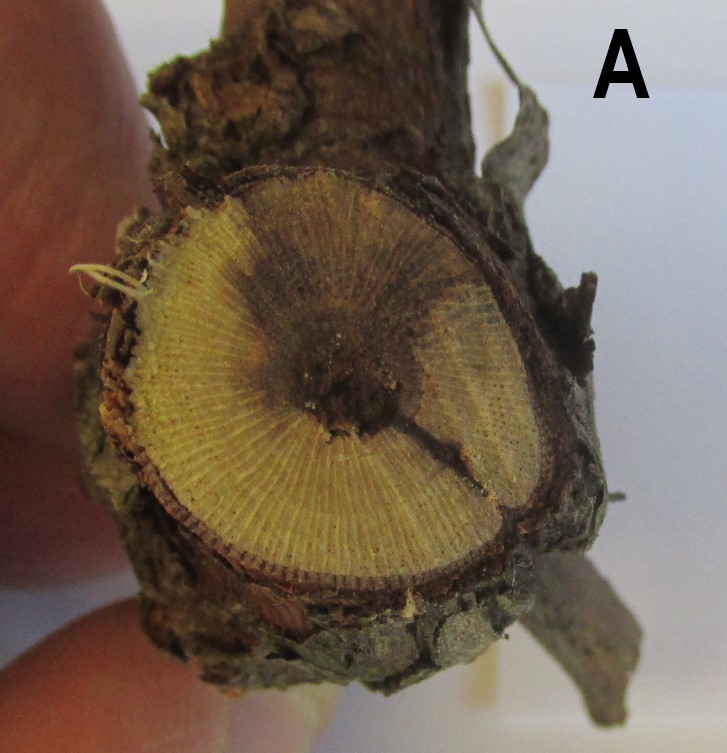

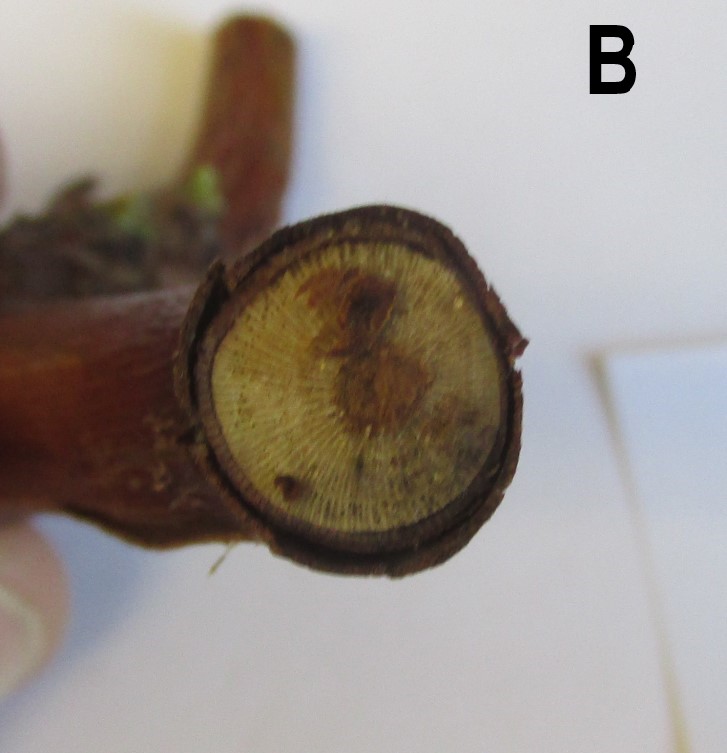

During Dr. Smart's visit to Missouri, he had the opportunity to dissect some grafted chardonel vines (Figure 1) that had not been planted in the field and some 2-year-old, field planted, grafted Norton grapevines. In all cases, the graft union of these grapevines was infected with grapevine trunk diseases. It is highly likely that the grapevine trunk disease is traveling from the infected rootstock to the scion. One option to reduce the incidence of infected planting material is to plant grapevines that are own rooted. As an industry, we need to work with nursery plant suppliers to reduce or eliminate grapevine trunk diseases from planting stock.

Other preventative practices should be undertaken to reduce grapevine trunk disease infections. These include vineyard sanitation and removing wild grapevines in the vicinity of the vineyard. Vineyard sanitation involves removing and destroying all dormant prunings from the vineyard floor. Wild grapevines can also be a source of grapevine trunk disease as evidenced from dissections of wild grapevines near vineyards in Missouri (Figure 2.F). How big a role wild grapevines are having in causing infections of grapevine trunk diseases is unknown at this time. This is one of the reasons why the samples collected during Dr. Smarts vineyard visits are important. Maybe the results will show that wild grapevines have a different complex of grapevine trunk diseases than cultivated grapevines. This result would suggest that wild grapevines infected with grapevine trunk diseases are likely not a great threat to cultivated grapevines as far as trunk diseases are concerned. Time will tell and I look forward to sharing the results with all of you.

I would like to thank Dr. Smart for his visit to Missouri. In addition, I would like to thank the Missouri Wine Research Marketing Council for providing funding to bring Dr. Smart to Missouri. Also thanks to the Missouri Grape Growers Association and the Missouri Vintners Association for hosting the field day with Dr. Richard Smart. Many thanks to the grape growers that participated in the field day and hosting Dr. Richard Smart at their vineyards.

Phytotoxicity: Be Careful With the Spray Cocktails

This week has been the week of phytotoxcity on grapes that resulted from tank mixing two or more pesticides together. I cannot say for certain that the symptoms growers are observing are the result of the pesticide cocktails. However, when new products come on the market and damage occurs to the crop, then I believe that growers should be informed of some potential problems.

There is also another issue that growers need to understand. The pesticide label often states some of the potential damage that can occur if the label is not adhered to fully. Obviously, pesticide companies cannot test every tank mix combination that growers may concoct. Therefore, if you are going to tank mix pesticides that have not been applied before then consider spraying a few vines and then observe them over a period time to determine if phytotoxicity develops.

The environment also plays a role in phytotoxicity. Weather conditions that delay the drying of the pesticide can result in phytotoxicity. These weather conditions can be described as wet and cool. Heavy dew and cool temperatures in the early am hours result in the pesticide(s) going back into solution on the leaf surface. The cool temperatures delay the drying of the pesticide(s) and prolong the period of time in which the pesticides may be absorbed by plant tissue. A common phytotoxicity that occurs during cool conditions is from copper. On the other end of the temperature spectrum, hot temperatures (> 85 degrees F) can induce sulfur phytotoxicity. Similarly, applying foliar iron sprays during hot temperatures can cause phytotoxicity.

Adjuvants can also play a role in phytotoxicity. If the label does not state that an adjuvant needs to be added then don’t add an adjuvant. A newly introduced fungicide product has the trade name Satori and has the active ingredient azoxystrobin which is the same active ingredient as Abound. In addition Satori also contains an adjuvant (Leci-Tech) which is derived from soybean. A grower recently tank mixed Satori, Rally and Assail and this resulted in phytotoxicity (Figure 1).

The take home message on phytotoxicity is the following:

- Read and follow the label.

- If applying a tank mix of pesticides that has not been applied before, then mix a small amount in a hand-pump sprayer and treat a few vines. Observe the vines for two to three days after treating to determine if phytotoxicity develops.

- Environment can play a role in the development of phytotoxicity. Environmental conditions that promote rapid drying of the pesticide on the plant surface is often beneficial.

- If the label of the pesticide being applied does not state that an adjuvant needs to be added, do not add an adjuvant to the spray solution.

- Plant growth that occurs during cool cloudy conditions results in thinner cuticles and this plant tissue is more prone to phytotoxicity.

Rupestris Speckles Masquerades Ability to Diagnose Early Downy Mildew Symptoms

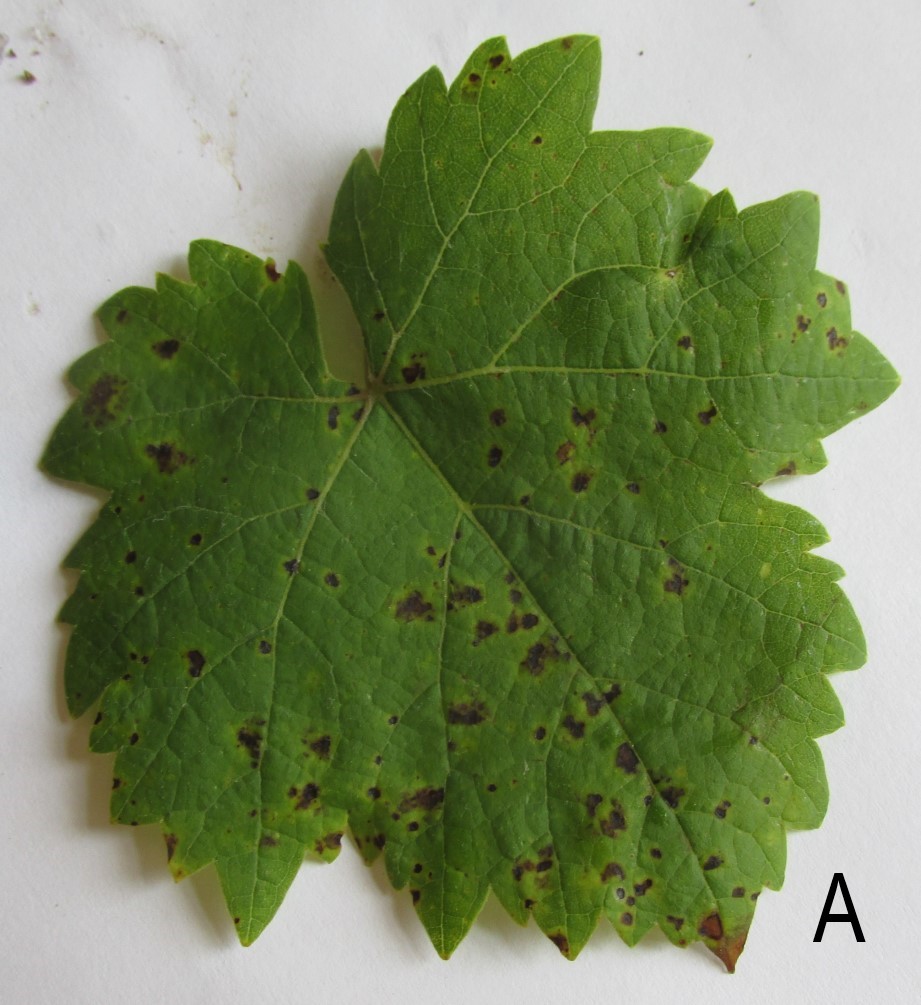

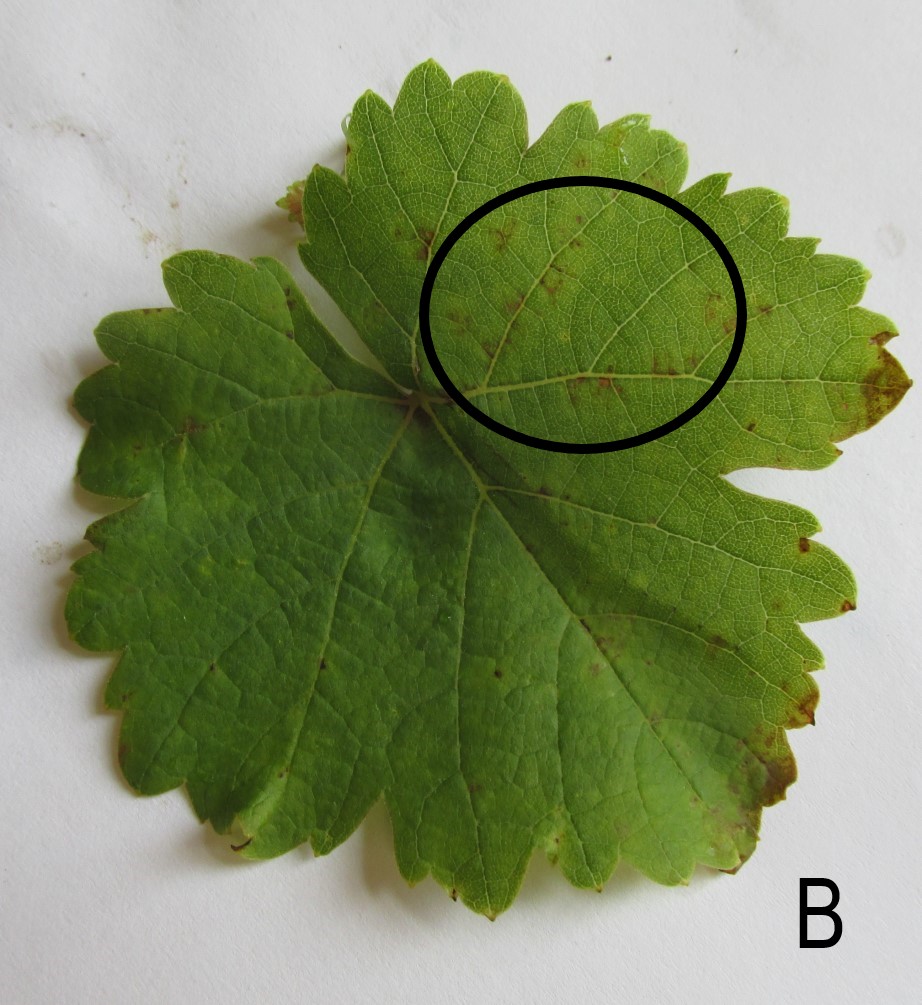

Valvin muscat expresses Rupestris speckles much more so than other cultivars that are impacted by this physiological disorder. In addition to Valvin muscat being susceptible to Rupestris speckles, the cultivar is also slightly susceptible to downy mildew. The initial symptomology of downy mildew is “oil spots” and these spots resemble Rupestris speckles. However since Valvin muscat is only slightly susceptible to downy mildew the oil spots can be overlooked as simply being Rupestris speckles. When environmental conditions are favorable for downy mildew infections do not overlook Valvin muscat as just having Rupestris speckles. Look closely at the leaves, since Valvin muscat is only slightly susceptible to downy mildew the symptoms may be masquerading as Rupestris speckling.

IA 20x Hand Lens Can Save You A Lot Of Misfortune

There is no doubt that having two grape diseases with mildew in their name can be confusing. Downy and powdery have the same last name mildew. Adding to the confusion are the fungicide control options with some products controlling only powdery or downy mildew.

Identifying which particular mildew you have especially during an outbreak is important because the fungicides used to control mildews are different. Potassium bicarbonate fungicides have activity only on powdery mildew. These fungicides are often applied to “burn out” powdery mildew colonies that are sporulating. The Potassium bicarbonate fungicides are not protective and will not protect tissue from powdery mildew infections.

Phosphorous acid fungicides have activity on downy mildew. The phosphorous acid fungicides are often applied when an infection period has occurred or when active sporulating colonies have been observed. When phosphorous acid fungicides are used as a curative, the higher label rate should be applied.

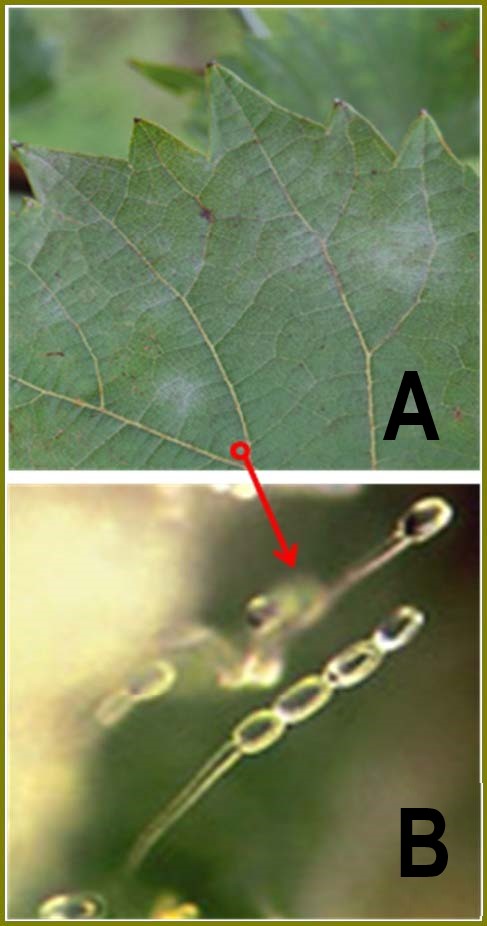

If infected tissue symptomology does not help you identify which mildew your vines are experiencing then resort to the 20x hand lens and observe the fruiting structures of the colonies.

Downy mildew fruiting structures appear as branched trees with round globes attached to the branches. The globes are termed sporangia and the branched tree structure is a sporangiophore.

Powdery mildew fruiting structures appear as small little barrels that are stacked on top on each other and supported by a single branch. The barrels are termed conidia and the single branch supporting the barrels is a conidiophore.

Grape Exchange

The Grape and Wine Institute will be listing grapes for sale starting on Monday, July 15, 2019. The grape exchange is a service to connect grape growers with interested grape buyers. All listings will be posted for 60 days unless updated.

If you would like to list grapes for sale, please contact Karissa King at kingkari@missouri.edu. You will be asked to provide the following information: cultivar, tons, contact name, email and phone number.

View the listings at gwi.missouri.edu/grapeexchange.htm.

Cumulative Growing Degree Days for the Seven Grape Growing Regions of Missouri from April 1 to June 24, 2019

| Region | Location by County | Growing Degree Days1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2018 | 30-year Average | ||

| Augusta | St. Charles | 1257 | 1449 | 1274 |

| Hermann | Gasconade | 1245 | 1408 | 1231 |

| Ozark Highland | Phelps | 1321 | 1511 | 1323 |

| Ozark Mountain | Lawrence | 1309 | 1495 | 1288 |

| Southeast | Ste. Genevieve | 1292 | 1454 | 1316 |

| Central |

Boone | 1246 | 1469 | 1244 |

| Western | Ray | 1138 | 1368 | 1203 |

1 Growing degree days at base 50 from April 1 to June 24, 2019. Data compiled from Useful and Useable at https://mygeohub.org/groups/u2u/tools. Click on link below to determine growing degree days in your area.

To determine the number of growing degree days accumulated in your area since April 1, use this tool.

Cumulative Growing Degree Days for the Seven Grape Growing Regions of Missouri from April 1 to July 1, 2019

| Region | Location by County | Growing Degree Days1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2018 | 30-year Average | ||

| Augusta | St. Charles | 1474 | 1664 | 1463 |

| Hermann | Gasconade | 1420 | 1588 | 1394 |

| Ozark Highland | Phelps | 1504 | 1700 | 1496 |

| Ozark Mountain | Lawrence | 1483 | 1690 | 1460 |

| Southeast | Ste. Genevieve | 1468 | 1639 | 1487 |

| Central |

Boone | 1434 | 1660 | 1415 |

| Western | Ray | 1324 | 1561 | 1371 |

1 Growing degree days at base 50 from April 1 to July 1, 2019. Data compiled from Useful and Useable at https://mygeohub.org/groups/u2u/tools. Click on link below to determine growing degree days in your area.

To determine the number of growing degree days accumulated in your area since April 1, use this tool.