Published on

Updated on

Viticulture News, Week of 16 June 2025

Columbia, MO

Contents:

- Yellow Speckle Viroid

- Rupestris Speckle

- Galls of grapevines

- Cumulative Growing Degree Days for Seven Grape Growing Regions of Missouri April 1 to June 9, 2025

Yellow Speckle Viroid

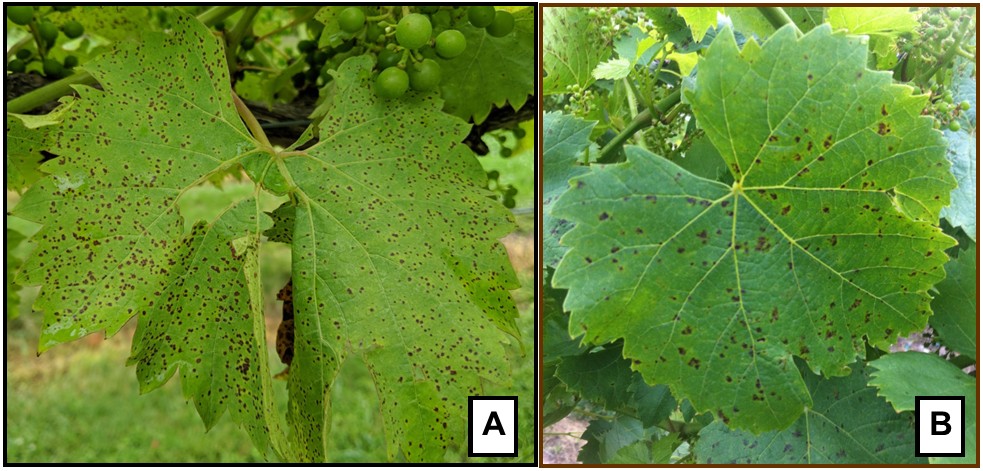

Pictures of symptomatic grape leaves were sent to the Plant Diagnostic Clinic at the University of Missouri on May 13, 2025 from Crawford County. MO. The cultivar was Cabernet franc and the leaves had yellow speckling that suggested that a virus may be the causal agent. The grower first noticed the symptoms on May 9, 2025. Based on the pictures submitted, the symptoms were representative of Yellow Speckle viroid. To confirm the causal agent, I met with the grower on May 21, 2025, and collected symptomatic leaf samples from Cabernet sauvignon (Figure 1) and Cabernet Franc. Results using molecular biology analysis confirmed yellow speckle viroid.

There have been five viroid’s identified that can infect grapevines. These include Hop stunt viroid (HSVd), Citrus exocertis viroid (CEVd), Australian grapevine viroid

Figure 1. Symptoms of Yellow speckle viroid on Cabernet sauvignon in Crawford County, Missouri on May 21, 2025. Photo credit: D. Volenberg.

(AGVd) and Grapevine yellow speckle viroid (GYSVd-1 and GYSVd-2). Our research has identified GYSVd-1 in samples collected from Crawford County, MO. The absence of GYSVd-2 in our samples is likely the result that GYSVd-2 has a low infection rate in cultivated grapevines.

Grapevines infected with GYSVd-1 or GYSVd-2 can display classic yellow speckling on the leaves or remain asymptomatic. Symptom development in infected grapevines has been shown to occur from increased light and temperatures. Interestingly, Grapevine yellow speckle viroid was first observed in greenhouse grown grapevines in Australia. The symptoms of an infected grapevine can be fleeting from year to year. Whereas an infected grapevine may show symptoms for one year and not the next.

Grapevines infected with only yellow speckle viroid typically do not have many negative problems. Issues arise when yellow speckle infected grapevines are impacted by other pathogens that results in a complex interaction that can reduce vine vigor and fruit quality. Currently, little is known how yellow speckle viroid interacts with grapevine viruses and fungal pathogens. To the best of my knowledge yellow speckle viroid has only been found and confirmed in Vitis vinifera. The absence of yellow speckle viroid and other viroid’s that can infect intraspecific cultivars is likely because intraspecific cultivars may likely remain asymptomatic and the fact that few if any states have surveyed for viroid’s using molecular analysis.

Rupestris Speckle

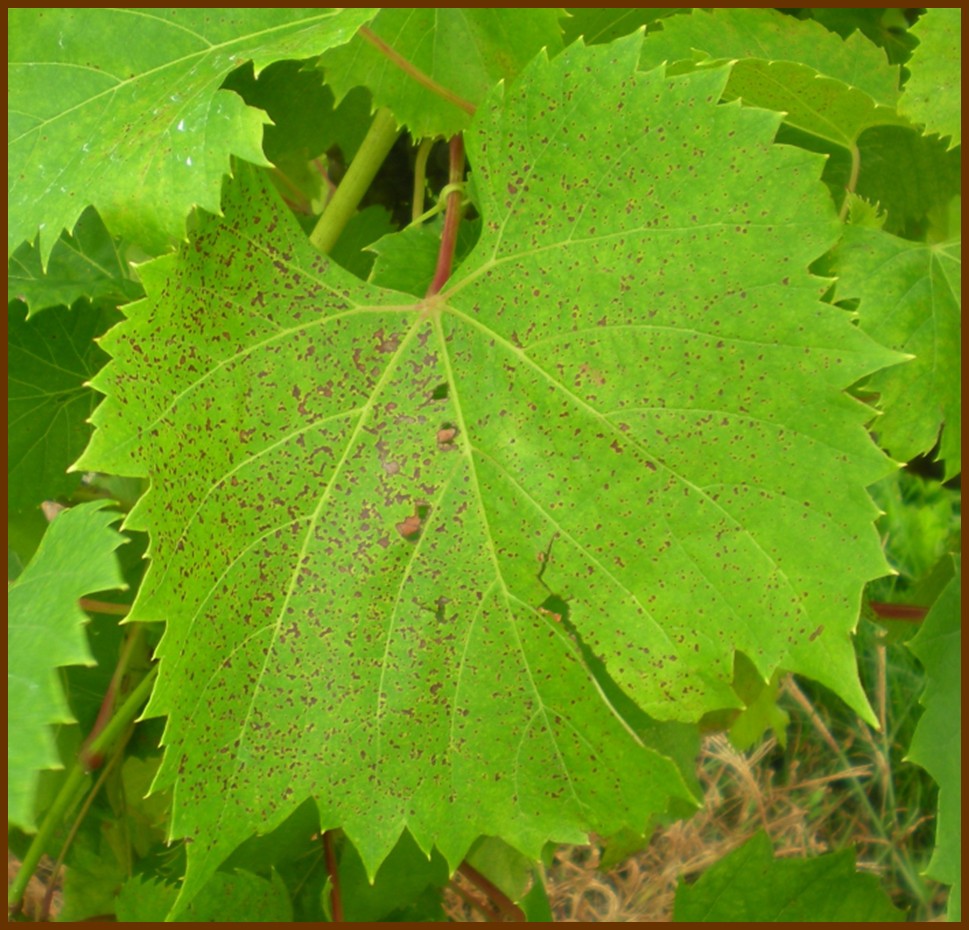

Rupestris speckle is a physiological disorder that causes dark spotting on leaves of intraspecific grape cultivars that have Vitis rupestris in their pedigree. The disorder causes small, circular to irregular, necrotic spots on leaves. In some intraspecific cultivars the necrotic spots may also have a chlorotic halo. Currently the precise cause of the disorder is unknown, but there is speculation that the disorder is caused by stress. These stresses may be abiotic such as drought or graft incompatibility or biotic such as viruses or grapevine trunk diseases. The disorder is believed to cause no impact on production. Being a physiological disorder there are no treatments recommended.

The disorder causes a diverse range of symptoms that is specific to the cultivar. In Missouri, Rupestris speckle is often observed every year in Chambourcin (Figure 2A) and Valvin muscat (Figure 2B). In Valvin muscat the disorder is sometimes referred to as muscat spot. The symptomology on Chambourcin is very similar to symptoms observed on V. rupestris (Figure 3).

The speckling symptoms can also vary within a cultivar as seen on Frontenac gris (Figure 4). Necrotic spots on leaves can be confused with black rot, a fungal disease caused by Guignardia bidwellii (Figure 5) You can differentiate black rot from Rupestris speckle by observing the lesions with a 20X hand-lens. Black rot lesions will have pycnidia forming within the lesion on the upper leaf surface (adaxial) (Figure 6).

It is important that you observe several lesions on leaves as black rot lesions will be in different stages of development. For example, a grape leaf infected with black rot will have some lesions with pycnidia and other lesions with no pycnidia. Also keep in mind the grape cultivar that you are observing. Both Valvin muscat and Chambourcin are susceptible to black rot.

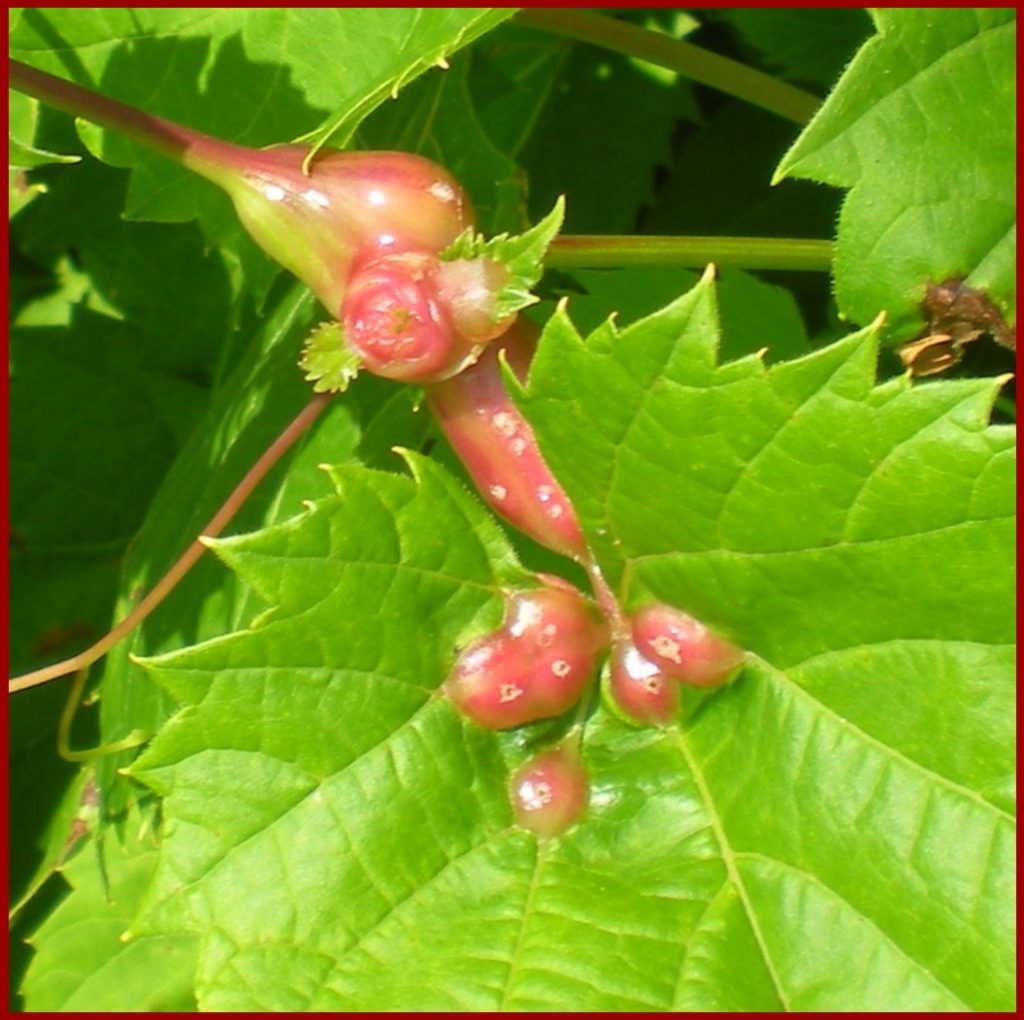

Galls of grapevines

There is a great diversity of galls that can form on the green tissue of grapevines. The most common and prevalent galls that appear year after year are leaf galls caused by foliar phylloxera, Daktulosphaira vitifolia (Figure 7). Some grape cultivars are highly susceptible to foliar phylloxera such as Frontenac noir, Frontenac gris and Frontenac blanc. Besides foliar phylloxera galls there are several galls that appear sporadically. In my experience these other galls appear when a prolonged period of cool temperatures exists during the period from bud burst through fruit set.

Figure 7. Galls on the backside (abaxial) of a Chambourcin leaf caused by foliar phylloxera, Daktulosphaira vitifolia. Photo credit: D.S. Volenberg.

A number of various shapes galls can occur on green grapevine tissue caused by small midge flies (family Cecidomyiide). The most visually noticeable gall is the grape tumid gall/grape tomato gall caused by a small midge fly Vitisella brevicauda (Figure 8). Gall formation can be initiated in many instances by egg laying (oviposition) by the adult form of the insect or by feeding by early instar larval stages. In the case of the grape tumid gallmaker the gall formation is initiated by the larvae feeding. Within the galls are small pinkish-red larvae.

Figure 8. Grape tumid galls/grape tomato galls caused by the midge fly Vitisella brevicauda (Cecidomyiide). Photo credit: D.S. Volenberg.

The larva will grow and develop within the gall and then form and exit hole in the gall (Figure 9). The larvae drop to the ground and complete their lifecycle. There are multiple generations (multivoltine) depending on environmental conditions. Although the galls appear unusual, the bright red nature of the galls draws your attention. Similarly, parasitic insects are also drawn to these galls and limit future populations of the grape tumid gallmaker.

Once galls have formed there is no chemical management option that will eliminate the galls. Mature fruit bearing grapevines can grow and produce grapes even with a great number of galls present. Galled tissue can be pruned off and destroyed to reduce future generations. In young non-bearing grapevines severe galling may increase the time to fruit production such as severe galling from foliar phylloxera. However, most galls on green tissue of grapevines are of little economic importance.

Figure 9. Larva exit holes are visible on the galls caused by the grape tumid gallmaker Vitisella brevicauda. Photo credit: D.S. Volenberg.

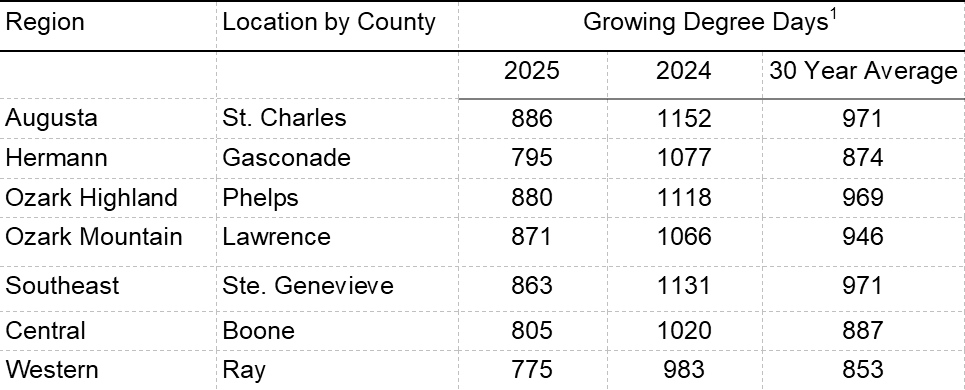

Cumulative Growing Degree Days for the Seven Grape Growing Regions of Missouri from April 1 to June 9, 2025.

1Growing degree days at base 50 from April 1 to June 9, 2025. Data compiled from Purdue Growing Degree Days

To determine the number of growing degree days accumulated in your area since April 1. Use this tool.

Please scout your vineyards on a regularly scheduled basis in an effort to manage problem pests. This report contains information on scouting reports from specific locations and may not reflect pest problems in your vineyard. If you would like more information on IPM in grapes, please contact Dean Volenberg at 573-473-0374 or volenbergd@missouri.edu