Published on

Updated on

Contents:

First Spray: Focus on Phomopsis Viticola

The start of the growing season of grapevines also marks the beginning of pest management. Casual agents that cause disease of grapevine tissues early in the season are well known. The timing and environmental conditions when these causal agents appear are also well known. In addition, we know which fungicides will protect the grapevine tissues from infection by these casual agents. One of the limitations in early season disease management is the very small application window that exists between one-half to 1-inch shoots and an infection period.

Springtime weather is unpredictable and often dictates when fungicide applications can occur. Heed the advice that your better off having your grapevines protected than unprotected once the phenology is one-half to 1-inch shoots (Figure 1). At this stage of growth, a limited amount of water carrier is needed to provide good coverage of the tissue. A total of 25 gallons per acre will provide coverage. The protective spray should therefore dry relatively quickly. A spray application just needs to dry prior to a wet period in order to be effective and avoid wash-off.

Once bud break occurs and green tissue starts to develop, this tissue needs protection. The biggest threat in the early season is Phomopsis viticola. Phomopsis needs free water on the grapevine tissue in order to cause infection. In April, this free-water may be provided by rainfall, dew resulting from the condensation of moisture in the air, fog or even water droplets forming from the grapevine through guttation. Next the causal agent needs to be present and since Phomopsis overwinters in lesions formed on last seasons shoots there are an abundance of spores. These lesions are often retained on spurs and therefore spores do not have to travel far to infect a developing shoot. Phomopsis is also a grapevine trunk disease and so older wood such as spurs, cordons and trunks can become Phomopsis disease reservoirs.

Phomopsis infection threat remains through approximately two weeks post bloom. At this time, the spores have been nearly exhausted. Phomopsis does not have secondary spores. Therefore, if your young shoots and leaves become infected there will not be spores produced and released from these lesions in the current season. The lesions that do form on your shoots can, however, become the source of next seasons spores if not removed during dormant pruning. So, the adage, “Start clean and stay clean.”

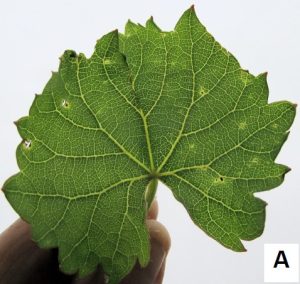

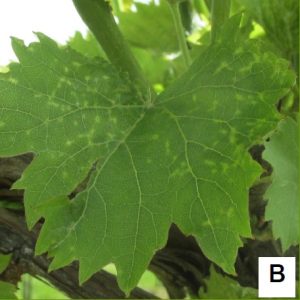

The take-home message for managing Phomopsis is understanding the causal agent is always going to be present in the early season. Also, weather conditions during the period of early grapevine growth are going to result in wet grapevine tissue. Phomopsis needs this wet tissue or free-water to cause infection. Lastly, a susceptible host is needed. Most all the grape cultivars grown in Missouri have some level of susceptibility to Phomopsis. In general, Vitis labrusca and V. vinifera are more susceptible to Phomopsis than hybrids followed by Norton, V. aestivalis. I say in general, because if your grape cultivar has had a problem with Phomopsis in the past then more than likely the Phomopsis problem will remain pretty persistent. Therefore, protectant sprays are needed prior to the development of Phomopsis disease symptomology (Figure 2). A best vineyard management practice is to determine if your protective sprays were successful. Scout the vineyard weekly. Early symptoms of Phomopsis on leaves are small necrotic lesions with a yellow halo. Even the lightest infections can be visualized by holding the leaf up to sunlight (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Phomopsis viticola infection on Chambourcin shoots (A) and Chambourcin leaves (B). Notice heavy infections of the leaf result in leaf distortion. Photo credit: D. S. Volenberg.

Figure 3. Low incidence of Phomopsis viticola infections can be visualized by holding the leaf into sunlight in the field (A) whereas heavy incidence of P. viticola are readily visualized on basal leaves within the grape canopy. A=Vignoles and B=Chambourcin. Photo credit: D. S. Volenberg.

Lastly, take some time to prioritize your first cover spray. Bud break and early growth are unpredictable. Similarly, local weather conditions are unpredictable. The first protectant spray should be prioritized to vineyard blocks with past Phomopsis problems, then V. vinifera and V. labrusca, then hybrids, followed by Norton V. aestivalis. Ideally, all these types of grapevines would get treated at one-half to 1-inch shoots. Typically, however, the unpredictability of grapevine growth and local weather interrupt the best made plans; it’s best to prioritize.

Mealybugs in Mid-Missouri Vineyards

Dr. Jacob Corcoran, USDA–Agricultural Research Service

Recent studies have demonstrated that the viruses that cause Grape Leafroll Disease (GLD) are widely prevalent in mid-Missouri vineyards. While it is not clear if GLD will significantly impact the American and hybrid grape varieties grown in Missouri like it has European varieties, steps should still be taken to limit the spread of these viruses between infected and uninfected grapevines. These viruses can spread to uninfected grapevines by grafting and by various “soft scale” insects. While several species of scale insects can spread the viruses that cause GLD, the grape mealybug, Pseudococcus maritimus, is the most common in the Midwest.

Female mealybugs, if present, are in vineyards year-round, however they are only active from early spring through late summer; during the winter months they are “hibernating” underneath the bark down near the trunk of grapevines. During the growing season, female mealybugs crawl (they don’t fly) around grapevines and feed on plant material using a sharp, straw-like mouthpart to suck up precious sugar from the vines. In the process, these female mealybugs can pick up GLD-causing viruses and spread them to other vines during subsequent feedings. Male mealybugs are capable of flying, do not feed, and only live for about three days (they emerge to mate, then die). Because grape mealybugs have two generations each season, there are two distinct periods during which male mealybugs can be found flying around vineyards looking for females to mate with. These periods represent opportune times to detect the presence of the mealybugs and to interfere with the mealybug life cycle.

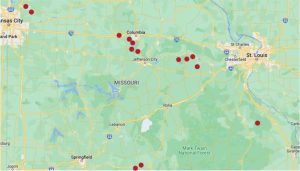

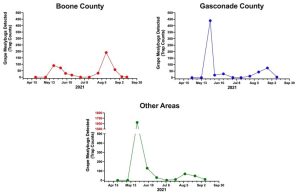

In April 2021, a monitoring program was conducted in mid-Missouri that utilized sex pheromone-baited traps to monitor grape mealybugs in vineyards. These traps emit a unique chemical that attracts male grape mealybugs from very far distances. Traps were deployed in 14 vineyards across mid-Missouri, from Kansas City to the Mississippi River, and checked every two weeks through August. The results from this survey revealed two important findings: first, that grape mealybugs were present in all 14 survey sites (Figure 1) to varying degrees; and second, that the reproductive male flights peaked during the end of May and mid-August, in 2021 (Figure 2).

The trapping data collected during the 2021 field season provides insight into male mealybug reproductive flights in mid-Missouri, indicating the short periods during the season where they (and adult females) are relatively exposed and therefore more vulnerable to chemical and biological control tactics. Control tactic application will likely be more efficient and effective if they are aligned with these periods of vulnerability.

In addition to monitoring grape mealybug populations and reproductive cycles in the 2021 survey, 56 field-collected specimens were tested using molecular techniques to verify species present and to test for GLD-causing viruses present in the mealybugs. All 56 field-collected mealybugs were verified to be the grape mealybug, Pseudococcus maritimus, and 10 were found to contain GLRaV-3, the main causal agent of GLD. Taken together, these data indicate that grape mealybugs are relatively widespread in mid-Missouri vineyards and that they are sucking up GLD-causing viruses from the grapevines they feed on. Because it is well-documented that grape mealybugs are capable of transmitting these viruses to uninfected grapevines, vineyard managers seeking to maintain GLD-free grapevines should develop grape mealybug control measures to prevent the spread of GLRaV-3.

The mid-Missouri mealybug monitoring program will continue during the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons. Vineyards interested in participating should contact Jacob Corcoran by email (Jacob.corcoran@usda.gov) to express their interest. This program is free to participants as it is funded by the MU Grape and Wine Institute.

Please scout your vineyards on a regularly scheduled basis in an effort to manage problem pests. This report contains information on scouting reports from specific locations and may not reflect pest problems in your vineyard. If you would like more information on IPM in grapes, please contact Dean Volenberg at 573-882-0476 or 573-473-0374 (mobile) or volenbergd@missouri.edu